Tunisia: Kaies Saied and Abir Moussi .. Are their rethoric populist?

24-12-2020 12:25:04

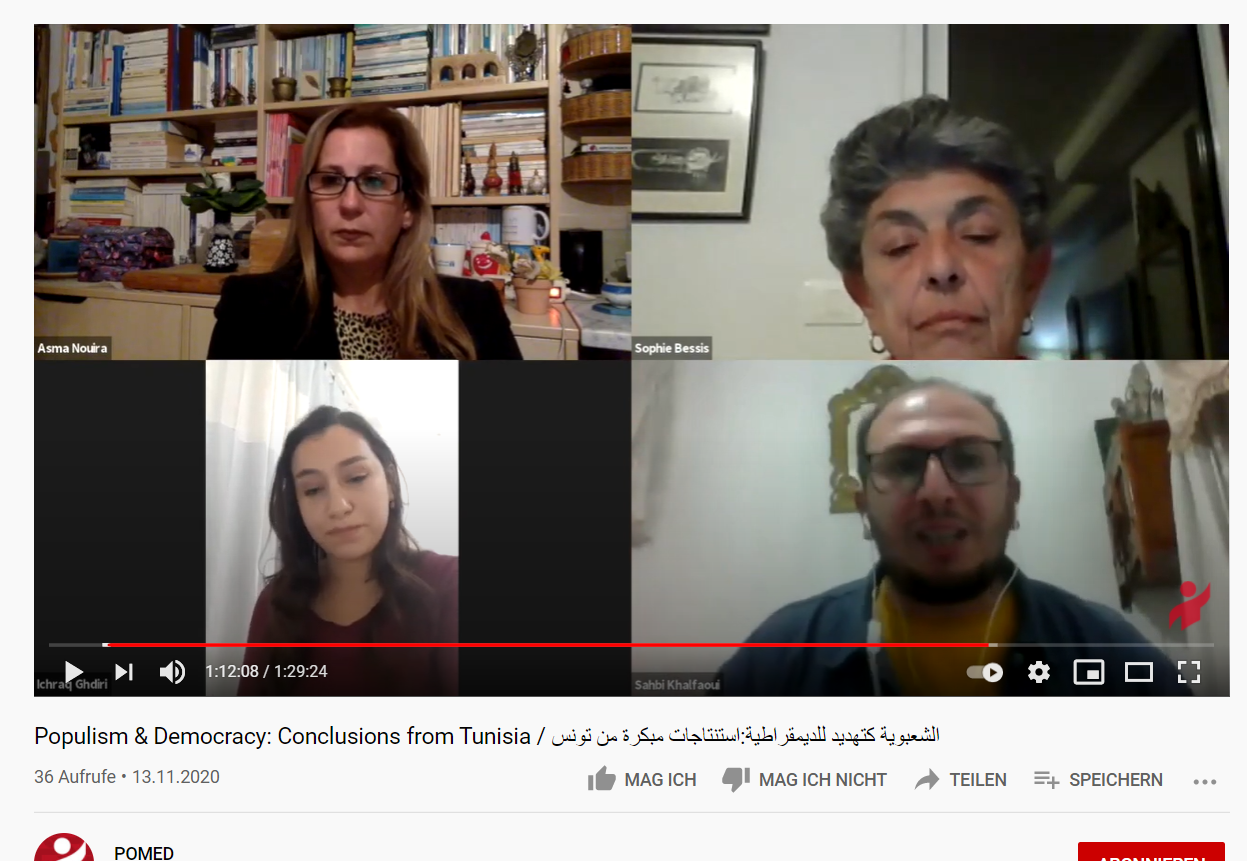

POMED Event Highlights: “Populism as a Threat to Democracy: Early Conclusions from Tunisia”

November 12, 2020

Panelists:

Sophie Bessis, Historian and writer specializing in sub-Saharan Africa, the Maghreb, Tunisia, and the status of women in the Arab world.

Asma Nouira, Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science in the Faculty of Law and Political Science at the University of Tunis-El Manar, specializing in the relationship between the state and Islam.

Mohamed Sahbi Khalfaoui, Lecturer at the Faculty of Legal, Economic, and Management Sciences in Jendouba and a member of the Tunisian Observatory of Democratic Transition.

Moderator: Ichraq Ghdiri, Coordinator of the State of Law Department at Solidar-Tunisie and a researcher at the Faculty of Law and Political Science in Tunis and former student activist at the General Union of Tunisian Students.

The 2019 presidential and legislative elections in Tunisia saw the rise of what many describe as “populist” parties and political figures who did not present a concrete platform but who did present themselves as “anti-regime.” This panel discussion explored the modern history and specificities of Tunisian populism, its central figures, and its discourse. It also explored how populism has affected Tunisia’s political transition and the dangers it represents for the country’s democratic aspirations. Below are some of each speaker’s key points, which have been edited for clarity.

How do you define populism? What are its fundamental principles?

Sahbi Khalfaoui: Two approaches deal with populism as a comprehensive global political phenomenon: the first is a discursive approach that considers populism as a unique style of political action. It is based on several factors such as discourse, fieldwork, and communication.

The second approach, and the one I personally adopt, is a conceptual approach that views populism as a thin-centered ideology which divides society into two opposing camps: ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elites’. Being a thin-centered ideology allows it to be combined with other, deeper and more established ones and to use their theoretical frameworks because it does not have comprehensive solutions of its own, resulting in a number of disparate types of populism.

The oppositional relationship between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ represents one of the fundamental tenants of populism. The people are portrayed as a homogenous oppressed group, lacking diversity and plurality, whose will has been hijacked. Likewise, elites are also portrayed as a single entity. Populists therefore continuously call on the people to reclaim their political will from the elites.

A second fundamental belief of populism is based on a particular vision of democracy. Populist movements see themselves as the sole defenders of democracy and people’s will, and believe themselves to be the embodiment of the people. The populist leader believes that the people’s will is also their own, and vice versa. Populist practices and ideas are therefore based on direct contact with the people, without intermediaries.

Populists also hold the belief that elites are corrupt and that the solutions to various crises are easy. Populism simplifies solutions and portrays democracy as complex. Finally, populism appeals to the public by evoking strong emotions.

There are different types of populism, both Left and the Right, but the most dangerous type appears to me to be the populism of businessmen, or neo-populism, which began in Italy with Berlusconi and continued with the rise of Donald Trump in the U.S., Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Nabil Karoui, here in Tunisia.

When did populism emerge in Tunisia and does it have roots in contemporary history? How do you evaluate the current political scene?

Sophie Bessis: Bourguiba’s regime was never a populist regime, as he never pitted the people in opposition to the elites. For him, elites had a mission to lead the people towards the achievement of independence and to bring the Tunisian people to a level of knowledge that would give them agency in their own development. For him, training and forming a national elite was a priority.

Populism, as it has been defined, appeared in the Tunisian political landscape after the revolution when the social question became central to the demands of the majority of Tunisians. Because the Tunisian Left did not take charge of the social issues that came out of the revolution, instead focusing their rhetoric on political and identity issues, what we saw was the emergence of a populist discourse that filled the vacuum left by the political class.

Nabil El Karoui’s populism is a political style and he has no ideology but rather changes alliances for his best interest. On the other hand, the current head of state, Kais Said, has made populism his ideology. His mantra, which is “the people want” serves as his ideology, and he is therefore totally convinced of the righteousness of this absolute pre-eminence of the people as he himself has shaped and which he does not represent but rather embody.

Populism does not provide answers to social questions, Kais Said for example, boasted that he had no election programme and said that it is the people who have a programme.

Populism, most often, is seen on the political right. In a certain way, it does not respond to popular demands that may be legitimate, but flatters what it believes to be popular instincts that are generally conservative and reactionary and this is why populist leaders in Tunisia are conservative, reactionary, or both.

Tunisian populism will last as long as there is no restructuring of the Tunisian political class to allow for programmes that are capable of responding, in a reasonable and reasoned way, to popular demands.

How does populism threaten human rights and individual freedoms in a fragile democratic transition?

Asma Nouira: Populism threatens liberal democracy and can lead to illiberal democracy and the tyranny of the majority. Those who come to power consider it their right to speak in the name of the majority as its representatives, because they have electoral legitimacy and thus have the right to restrict rights and freedoms, and persecute minorities by limiting their rights because of their opposition to the majority, or because they demand those freedoms.

The 2019 presidential and legislative elections allowed us to witness the phenomenon of populism because it allowed populist forces access to the decision-making centres at the parliamentary and executive levels.

The success of these populist forces and of populist discourse represents a manifold crisis in Tunisia: the crisis of representative democracy and the crisis of the elites in the context of a still broader crisis playing out at the political, economic, and social levels. This, as corruption continues to spread, unabated, fueling populist discourse.

Populism in Tunisia has forced us to move directly from a democratic transition to a crisis of democracy, having effectively lost a stage as we did not establish democracy before entering into a crisis.

The denunciation or criticism of elites is common in various types of populism, especially in dissident populism, whose discourse is based on criticism of the elites and their portrayal as a fundamental enemy of the people. This includes all elites: political elites, but also cultural elites and human rights elites. All elites are the main enemy of the people because they are believed to be corrupt and the people are their victims. On the other hand, one of the outcomes of this anti-intellectual tendency is the glorification of the people’s knowledge, for the people are more knowledgeable than their leaders, intellectuals, and the elites, and know their own interests better.

The Tunisian public’s conservatism is related to its religious identity and in this context this identity conflicts with individual freedoms such as freedom of conscience, equality in inheritance, freedom to choose one’s partner, homosexuality, the death penalty, etc. Therefore, we find many populist political actors, who may have a human rights background or whose parties’ founding statements are based on human rights principles, adopt positions that are antithetical to these principles in order to satisfy the conservative character of the people. Others, like Kais Said, seek to use their political discourse to persuade the public that questions of rights and freedoms are foreign dictates, and imposed by the European Union, for example, bringing issues of sovereignty and conspiracy theories to the forefront.

With populist powers being in decision-making positions the Tunisian legislation will be incompatible with the Tunisian constitution, especially in its first chapter on rights and freedoms as these populist actors might pass laws that limit freedoms.

Copy rights: https://pomed.org/pomed-event-highlights-populism-as-a-threat-to-democracy-early-conclusions-from-tunisia/